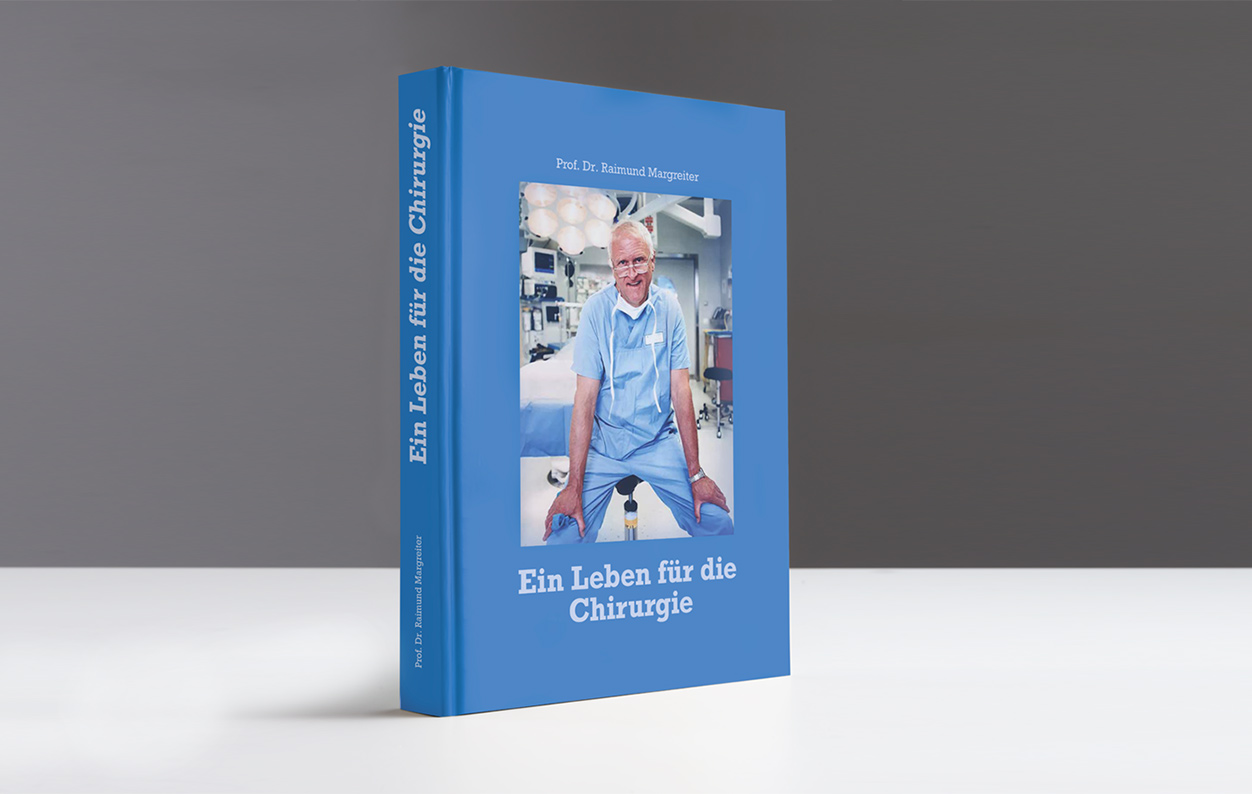

The Life of

Dr. Raimund Margreiter

The breathtaking career from resident doctor to the Chairman of the Board of the Innsbruck University Hospital for Surgery. As a "self-taught" person, Dr Raimund Margreiter began with kidney and liver transplants, later performing combined heart, lung, intestine and even hand and forearm transplants, for example. "The only transplant surgeon who has done it all", is what is said about him in the international medical community. In addition to these sensational organ transplants, he was a versatile surgeon. He achieved a great deal, especially in tumour surgery, and was also very committed to basic research.

// Professor Margreiter, you are considered a pioneer of modern medicine in Austria and Europe. In transplant surgery, you have made history with courageous operations. What has driven you?

Dr Margreiter: Courage was actually not at the top of the list. When I started as a resident doctor in the Department of Surgery at the University Hospital of Innsbruck after my studies, there was a certain need for action there. The first senior physician at the Department of Vascular Surgery wanted at that time to set up a kidney transplant programme and asked me if I would join in. I was known as someone who worked hard, got things done and moved things forward - I already had that reputation back then.

// How old were you?

Dr Margreiter: I was quite young at that time, 31 years old. It was an honour for me to be part of such a programme at such a young age. We observed a team of doctors in Munich, how they proceeded with transplants. We said to ourselves: we can do that, too. However, a lot of preparations still had to be made in Innsbruck. Then, of all things, the senior physician who got me into the programme got a scholarship and went to the USA for a year.

// What did you do?

Dr Margreiter: We agreed that I would prepare everything. After his return, we wanted to start with the clinical programme. He did come back after a year, but he fell out with the hospital management and left the hospital. That left me alone, without support, without infrastructure, very young. And not everyone in the hospital was enthusiastic about the project. On the other hand, I had invested a lot of work in the preparations. And I didn't want that to be in vain.

// How did you save the project?

Dr Margreiter: There were three doctors who were willing to assist. But we had no other support. And I had no right to give instructions, everything was on a voluntary basis. That's how we started transplanting. You asked at the beginning what drove me. When I start something, I want to finish it successfully. And we succeeded. After a while, our transplant programme was one of the best in the world.

// Your medical successes are legendary. You are the only surgeon in the world who has transplanted all so-called solid organs, from the kidney to the heart.

Dr Margreiter: The first three transplants were surgically successful, but the organs were rejected. But we got a good handle on that. The fifth kidney in January 1975 is still working today, 46 years later. After that, we applied our knowledge to other organ transplants. First the liver, then the pancreas and in 1983 the heart. That year we also successfully performed the world's first combined liver-kidney transplant. This patient is also still alive today.

// The achievements have apparently spurred further research into new and better therapies and treatments.

Dr Margreiter: At that time, the vision was born to set up a department where replacements are created for every form of organ failure, be it temporary - that is, for a certain period until the organ has recovered - or permanent, which then usually leads to a transplant. And we’ve succeeded in doing that. We developed an artificial liver and an artificial heart, but neither of them ever made it to finished product status due to a lack of money. Then we worked with the commercially available devices. With this department, we’ve achieved a unique feature that no one else has done.

// Professor Margreiter, you come from a medical family. Was it always clear to you that you would become a doctor one day?

Dr Margreiter: Five of my ancestors from my grandfather onwards were doctors. And because I have the same first name as my grandfather, many people said: This will be the new doctor from Fügen. When I was about to take my school-leaving exams, I thought about maybe studying law or architecture. In the end, I decided to go for medicine. When I did an internship in surgery before my doctorate, they asked me to stay longer. I liked it there so much that I decided to become a surgeon.

// Everyone can read more about your numerous triumphs in your biography „Ein Leben für die Chirurgie“ ("A Life for Surgery"), which has already been published. But your limited free time with daredevil mountain tours was also plenty adventurous, wasn't it?

Dr Margreiter: In fact, medicine, was always the centre of my life. But I was fortunate to be invited to join a mountain climbing expedition in the Andes in South America in 1969. When you’re invited to join an expedition with the best mountaineers, it’s difficult to say no. The expedition was a success, so more invitations followed. However, such activities have always been a secondary matter for me and limited to my official holidays. Only once did I make an exception.

// What was the exception?

Dr Margreiter: A Himalayan expedition with Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler to Mount Everest. For that I took unpaid leave.

// Strictly speaking, however, you also worked at the same time. Climbers like to tell the story that you saved the life of an injured Sherpa with an emergency operation. How is it possible to operate in such an inhospitable environment?

Dr Margreiter: The Sherpa had suffered an open skull base fracture when he fell into a 45-metre crevasse. In addition, there were other fractures, on the right arm, the left thigh and the chest. He survived. However, the environment there is not as inhospitable as you might think. The base camp is at 5400 metres, but there was enough space in a tent to lay the Sherpa down and take care of him. We also had the necessary instruments and medication with us.

// Professor Margreiter, medicine has developed incredibly over the past decades, not least because of outstanding personalities like you. What advice do you have for young people who want to become doctors today?

Dr Margreiter: In surgery, just as in many other disciplines, almost everything has been done. In 2000, for example, we were already transplanting hands. Today, progress comes from the laboratory, where the exciting developments take place that lead to new therapies. I can only recommend to every young person that they get involved in that field.

// Is there still enough room for a pioneering spirit in today's technological and digitalised world?

Dr Margreiter: Absolutely. This pioneering spirit must be applied above all in the laboratories, where there’s still a lot to do. I assume that medicine will be completely rewritten there in many fields. Just take the progress in oncology, it's enormous. The opportunities are there, but what worries me is an increasingly widespread attitude in the next generation.

// What specifically bothers you?

Dr Margreiter: Especially an operative discipline like surgery can only really be fun if you’re truly well-trained and operate with few complications. In view of existing working time regulations, however, it’s hardly possible to get a broad and well-founded education. In addition, there’s a pronounced urge for work-life balance. I know of hospital departments where half the doctors only work 20 hours a week because they prefer to go skiing in winter and climbing or cycling in summer. In this way, medicine degenerates into a job. We need a different mindset in the young generation, as they like to say today. Only then can you achieve top performance in medicine.